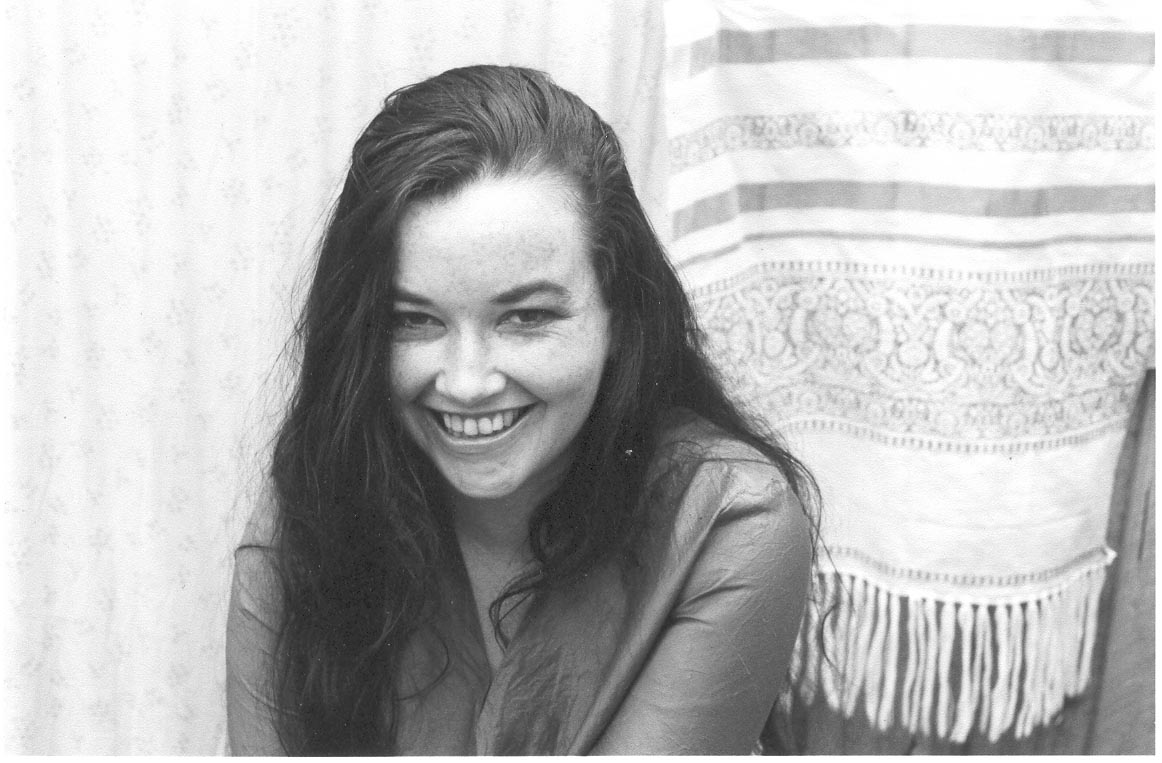

Paola Bilbrough, New Zealand. Bio: Paola Bilbrough was born on Waiheke Island in 1971. Her first book, Bell Tongue was published by Victoria University Press NZ in July 1999. An excerpt was republished as part of an American anthology entitled, Wild Child: Girlhoods in the counter culture (Seal Press). Her work has also appeared in various Antipodian journals including, Heat, Cordite, Westerly, Imago, Sport, and Landfall. |

Two men. 1. He marveled at her skin's softness. Longing for another, she replied, 'there are thousands with soft skin.' Nick was returning to Brisbane: warm sea and rain, fruit heavy on the tress. No time for recompense. His cousin, a gardener, was bearded, sleepy-eyed, alert to his own beauty. Two men sat on the sofa, ice-blue polish on their toe nails, skin wine-flushed. Everyone wanted a part in their silent dialogue. 2. The cousin, Darragh, lay in Nick's room beneath a white sheet, the knowing calm of a religious icon. Nick sat on the edge of the bed, eyes huge, indigo and Darragh said tell me a story, you know I love stories. She imagined his hands cupping heads of flowers. A voice in her cried I can tell you stories but she left without speaking, the two men outlined behind orange rice paper. Bones It was her throat - the way it filled with humour, arched back, gleamed across the room. And bones: a fractured tibia and fibula The sounds entering him as she spoke, vaguely botanical like the names of alpine voilets. He worked the syllables into a song with her wool chiffon dress the colour of a mountain pool, the dark pink resin bracelet - a spine of silver inside. He tried it on his own wrist, the small click as it bit bone. And he kept thinking of hers - the violence of a somersault - how her bones cracked beneath her. He felt the fall in his own body, snatched a breath, ankle swelling within the boot and everywhere her hair. She made him bread and the dough - separated in strands to braid - looked like bones against black tray, yet had the pliable warmth of flesh. He imagined holding her pelvis, sinking his mouth deep, the notches of her hips evident beneath the stretch of skin. Relief for Maria Zajkowski A sweatband on her wrist, a faux fur hat, her nose a crescent, lips slightly parted in a room of masks and Madonnas. Gazing at the plaster relief of two retrievers over the heater, she waits for a poem to take shape in her. The dogs are without feet, legs sinking into marshland. Drinking out of Poole china, a half pear on a plate, black seeds like eyes. All of this clamouring for attention as she begins to write of ice, ancestors and a coat with striped lining, bone buttons, moth nibbled cuffs. A coat her grandfather was not allowed to take. It's this garment that's the sticking point. As if she were stitching a winter scene: the woman's grey wool stockings, a railway platform. These details are clear but the coat and destination - Siberia - are burs and the needle will not go through cloth. He didn't take the coat and much later one of his sons - a small boy - arrived alone in a distant country. There's relief in poems; the forming of a line, an internal rhyme, shapes and colours below ice. Relief in ordering something untidy and monstrous. She can see the coat, knuckles white against charcoal wool as he hands it over. She takes a brush and paint. The dogs are a bland, random shade - she colours them Byzantine gold, lapis sky behind and, thinking of the coat, she paints in the dogs' unformed paws. Residue Sometime in the eighties my father cut his hair, bought false teeth, gave away his homespun jerseys. Our hitchhiking days were over. Yet there was a residue: an insistance on chopsticks, barely known guests: a playwright from Dundee who never bathed, a woman trapeze artist who smoked a pipe, others who slept on the floor, talked into the night. My father sat in bed and wrote, typewriter on lap. Above a child's drawing of an armless woman, a painting of two men kissing; one blue, the other pink and white. Hardly a less peripheral existence than before, only now we were anchored by a house. Then Alice; slim and pale as a stem of wheat stepped into the disorder of our lives. There were fewer guests. Alice wore red, sat cross-legged, a row of polished stones at her throat. Voice filling the rooms as she called my father's name from the garden. The last guest, my mother returned from Paris. She lay with a fever as my father juiced chickweed and carrots. Alice's pressed, cotton shirts, bobbed hair emanated capability. my mother, stubbonly, a child. At dinner all three sat as if at a bus stop, raising their implements in unison. I sat opposite, thought of Alice's inheritance: our past unchosen by her, spoken in gesture, in the scrape of chopsticks on china. Swathed in memory I leant against the rose-papered wall and it collapsed, sodden against my back. All works copyright Paola Bilbrough |

BMP nzpoetsonline |

BMP nzpoetsonline |